Saturday, July 31, 2010

Прогноз погоды... ЖАРА!

Thursday, July 22, 2010

Stories from the road...

During my stay in Moscow, in May 1889, I found out that Tolstoy was getting ready to go to Yasnaya Polyana, and he wanted to go there on foot, as he had done several years ago with Kolechka Ge and Dunaev. I suggested he go with me. Lev Nikolvaevich agreed, and we had decided on the day of our departure. On the appointed day [May 2, 1889], I arrived at Khamovniki [Tolstoy’s Moscow residence]. Sophia Andreevna had gotten Tolstoy ready for the road. She gave me instructions on how to take care of Lev Nikolaevich while on the road. We got into the carriage and drove off. The driver took us out of town.[i] He let us out and we set off on foot.

Recounting about this trip, I cannot remember all the details and the order of events. In my mind there are only confused fragments of memories. (It was almost 50 years ago, after all). I will describe it as I remember it. We asked permission to sleep in one hut. Since many pilgrims passed along the Kursk highway, it was common for the residents to let people stay the night. The hostess ushered us in willingly and the started up the samovar. Tolstoy went on the porch and sat down. I stayed in the house, since the entire trip I tried to provide him with time alone as often as possible. It was a beautiful May evening. In a nearby garden the nightingales were rustling. When the owner put the samovar on the table, we crumbled baranki [round, crispy biscuits that look like bagels]. moistened them with boiling water, and when they were steaming, added some milk. It turned out to be a dish that Tolstoy really appreciated. We walked beside the railway line, along a path that ran alongside.

Once we came to three passers-by, apparently tramps [босяки, “barefoot wanderers”], who were kindling a fire and and cooking something. Walking past them, Tolstoy said:

“Greetings, brothers!”

“Your brother’s a dog,” one of them said sullenly. We walked a few steps. Tolstoy stopped, as if he wanted to return to the speaker, but then changed his mind, and we went on.

We went along the road (the highway crossed the railway several times) and down a hill. Lev Nikolayevich, pointing to a village, said:

“When we came here with Kolechka and Dunayev [in 1888], a squealing pig ran out of that yard, all covered in blood. They had slit its throat, but hadn’t finished it off, and it had escaped. It was terrible to look at it, probably most of all because its naked pink body was very similar to human’s.”[ii]

At another point, when the dusk had descended upon us, a woodcock flew straight at us, but when it saw us, it got scared and made a sharp turn and disappeared into the woods. Tolstoy said to me:

"You know it ought to have he flown right up to us and sat on a shoulder. It will be that way someday."

One day it was rainy, the road became difficult, and we set off to spend the night at the estate of a Moscow friend, the merchant Zolotarev. It was a long way before we would reach our resting place, so we had to hurry so as not to caught in the dark. Tolstoy walked quickly with his light tread, and it was hard for me to keep up with him. Turning off the highway and going two kilometers, we finally found the estate. The owners were home and received us, tired and soaked. Having sat for a bit, I felt that I was feverish from exhaustion. They put me to bed and started warming tea. Tolstoy said that the best way to get warm it is to play a piece for four hands, and immediately sat down with the hostess at the piano. Before going to bed I still heard him speaking with the hosts, telling them how to grow red currants. The next day I felt fine, and we went on.

When we passed through Serpukhov, we stopped at the post office. Lev Nikolaevch asked for the letters in his name. (Sophia Andreevna had intended to write him there.) Suddenly everyone in the post office got worked up; the employees and the public all whispered and looked at Tolstoy. I do not understand how Tolstoy could bear all the attention. He wrote a postcard, dropped it off, and we went on.

After five days we reached Tula. We went to the house of the vice-governor Sverbeev, whom Tolstoy knew quite well. We were welcomed, fed and put up in a room where the two sons of the host, marine cadets, usually lived. In the morning when we got up, Tolstoy noticed some huge iron barbells under the bed. He took them and wanted to do some exercises. I was afraid that that at his age [Tolstoy was 61], he would hurt himself, and I protested. He put down the weights, but said:

“Well, you know I have lifted five poods [two-hundred pounds] with one hand.”

From the conversations with Tolstoy during my time with him can recall only two fragments. We were standing on the second floor balcony and looking across the garden to the east. There, at the edge of the garden, stood two pine trees. Tolstoy said: “My brother and I planted those two pines, and we asked ourselves whether they would ever grow to the horizon… And now they are so far above it.” Another time, in a conversation about life after death, he said: “I know that I will live with such exalted beings, ones that we cannot even imagine now.”[i] . Tolstoy is more precise—he mentions in his diary that they took a carriage ride to Moscow’s toll gate, presumably the Serpukhov Gate—located close to the Tul’skaya Metro station.

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

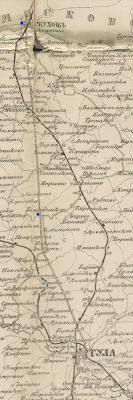

Cool old map of Tula province...

I found this map on a Tula historical society website. (Click on it the map to the left for a larger image, or go to the original site, which has a GINORMOUS map)

Bolotov & Dvoryaninovo

Thursday, July 15, 2010

What did Tolstoy take?

We have a pretty good idea of what Tolstoy took on his first walk, based on accounts left by Anna Seuron, the children's governess and German instructor. Seuron is an invaluable source of details about the Tolstoy household during this time: Tolstoy wasn't making many diary entries, and he had yet to attract the troupe of Boswells that would record his every move from the 1890s until his death. Seuron, however, is pretty unreliable: Her memory for detail is weak, and she had an ax to grind with Sophia Andreevna, as Seuron was also fired as governess for striking one of the children.

In his homemade boots, he decided to set off for his native estate. He prepared for the trip, taking only what was necessary. He put on a linen bag for bread, packed a shirt, two pairs of socks, several handkerchiefs, and some stomach drops (his stomach often bothered him). To that add a little notebook with a pencil tied to it for notes along the way. In such a way, he set off accompanied by three young men, two from aristocratic families and the third, the son of the Russian painter Ge (Gay). The two aristocrats didn't make it. Only the Count and Ge continued on with some privations, begging in the villages and arriving at the estate without a cent. No one recognized the Count there, which made him very happy.

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

Tolstoy's first long walk...

"Let's go into the last hut," said the count. "It's closer to the road."We approached the house. A mean black dog ran up to us, but did not bite. Hearing the barking, an old woman came out of the house and chased the dog into the courtyard. The old woman was covered with a dirty blue shabby cloth; she was thin, dressed in a blue shirt and а skirt of white coarse linen, barefoot."Granny, let us spend the night," the count asked her.

"Father, I am glad to host wanderers [stranniki], but I don't have anywhere to put them. It's hot in the loft, and the flies won't let you sleep. And we don't have beds.""We don't need a bed," the Count. "Bring us a bundle of straw in the seni*, we'll sleep there. Do you perhaps have a samovar, milk and eggs?"

"I have all that, sir."

"We do not need anything else."

"Well, sir, if you don't mind sleeping in the seni, then you are welcome."

The old lady treated us simply and cordially, and, apparently, liked to host wanderers. At her bidding, we entered the house, dropped our packs. The Count took off his coat and remained in his linen blouse. I asked her to bring out the samovar, a jug of milk and a dozen eggs. [...]

The tea was ready, the eggs were boiled in the samovar. On the table stood a pitcher of milk with cream from the top. The old woman said it was a good milk, milked early that morning. I asked for a mug, took some cream for the Count, then whittled him a little spatula from scrap wood in place of a spoon for the eggs. Everything was ready on the table, and the old woman brought from the cellar a whole loaf of bread and gave us to slice as much as we need.The Count invited the old woman to drink tea with us at the table, and she was very happy and did not refused, but said: "Drink to your health, but I will probably drink just this one cup. It's nice to warm these old bones."They started on the tea and eggs. Tolstoy sat on a bench under the icons, me across from him on the bench, the old woman to his left side at the corner of the table. The Count had a glass of tea and went to sit out on the porch to avoid the heat and flies and write in his notebook.

Friday, July 9, 2010

Tolstoy's first blog entry

1886 г. Апреля 5. Подолъскъ.10 часовъ утра, въ Подольскѣ. Ночевали и идемъ здоровои весело. Стах[овичъ] разбился ногами и подъѣзжаетъ. Ждуписьма въ Серпуховѣ. Целую всѣхъ. У насъ ужъ одинъпостоянный товарищъ - мужичекъ.Л. Т.1886. April 5. Podolsk.It's 10 in the morning in Podol'sk. We spent the night and we're walking well and happily. Stakhovich's legs broke down on him and he's caught a ride [on the train]. I await your letter in Serpukhov. My love to everyone. We already have one constant companion--a peasant chap. L.T. [Tolstoy]

Нескольно слов из Подольска меня совсем не удовлетворили: промонли ли, устали ли, сыты ли, где ночевали, ничего не известно.

A few words from Podol'sk does not satisfy me in the least: Did you get soaked? Are you tired? Are you hungy? Where did you spend the night? I don't know a thing.During this period, the mid-1880s, Tolstoy picked up his diary after a decade or two of not writing much... He becomes something of a graphomaniac, filling nine volumes of his Complete Collected Works between 1885 and his death. (Keep in mind that each volume is a thousand pages!) I'll publish some more excerpts from his diary of the period next.

Caricature from 1907

.gif)

These walks that Tolstoy did became part of his legend... A restless man, a man of the people, an adventurer.

About the walk...

Leo Tolstoy, “great writer of the Russian land,” author of War and Peace and Anna Karenina and scores of other literary works, prophetic leader of a revolutionary worldwide movement, was a fidget. After a morning cooped up writing, he loved nothing more than a long walk, a ride on his horse, an afternoon hunting.

In early spring of 1886, when he was nearing sixty, Tolstoy decided to walk from his Moscow home to his ancestral estate, Yasnaya Polyana, outside of Tula, a distance of more than two hundred kilometers. “I am walking, mainly, to recuperate from the luxuries of life and perhaps to take part a bit the real life,” he wrote a friend.

He left, without a clear plan, a pack on his back and a couple friends at his side. He spent the nights on the floor of peasant huts, often sleeping with a dozen other travelers. He ate bread and cabbage soup. He gathered material for future stories. “It was, as I’d assumed it would be, one of the best memories of my life,” he wrote his wife upon arriving at Yasnaya Polyana, complaining of “a little tiredness.”

In August 2010, two American professors of Russian literature, Michael Denner (Stetson University) and Thomas Newlin (Oberlin College), will retrace Tolstoy’s journey, arriving at Yasnaya Polyana on August 11to attend a international Tolstoy conference.